Across Europe and North America, some of the most celebrated museum collections rest on an uncomfortable truth: they contain thousands of African artworks that were stolen, looted, or taken under highly unequal conditions. Labels may describe them as “gifts,” “acquisitions,” or “finds,” but behind many of these objects lie stories of invasion, coercion, and quiet theft.

One recent case that made headlines is the story of the Ife head, a bronze masterpiece from Nigeria. Its journey through European hands reads less like the life of a museum object and more like a crime file.

The Ife Head: A Stolen Masterpiece in European Hands

The Ife head was stolen from the Jos Museum in 1987, one of nine national treasures taken in a single break-in. In the 1980s and 1990s, Nigerian museums were repeatedly targeted by thieves, often aided by internal collaborators and international dealers eager to feed a growing market for African art.

How the Ife Head Was Stolen in 1987

Then, in 2007, Belgian authorities publicly auctioned a number of confiscated artworks. Among them—astonishingly—was the Ife head, despite its long-standing identification as stolen Nigerian property. Soon afterwards, the same artifact resurfaced in Britain, where it ended up in police custody. The exact route it took from Belgium to the UK remains unclear.

Why Its Return to Nigeria Remains Delayed

Yet two questions are painfully obvious:

- How did a clearly stolen Nigerian artifact end up in Belgian hands in the first place?

- If its provenance is well documented, why is its return to Nigeria still “under review” rather than already completed?

The Ife head is just one piece. But its fate points to a larger reality: Africa’s cultural heritage is still entangled in European legal systems and market logics that rarely favour return.

A Continent’s Heritage in Foreign Vaults

Scholars estimate that around 90% of Africa’s cultural heritage is held outside the continent, mainly in European and North American institutions. France’s Musée du Quai Branly alone holds around 70,000 African objects, while the British Museum and other UK institutions hold tens of thousands more.

90% of Africa’s Cultural Heritage Resides Abroad

These are not just “artworks.” They include royal regalia, sacred objects, ancestral figures, ritual instruments, and everyday items whose meanings are rooted in African cosmologies and social life.

Why Western Museums Resist Restitution

Today, many Western museums claim their hands are tied by national laws, donor agreements, or fears of “emptying the galleries.” Yet for African countries and diaspora communities, the issue is simple: what was taken without consent should be returned.

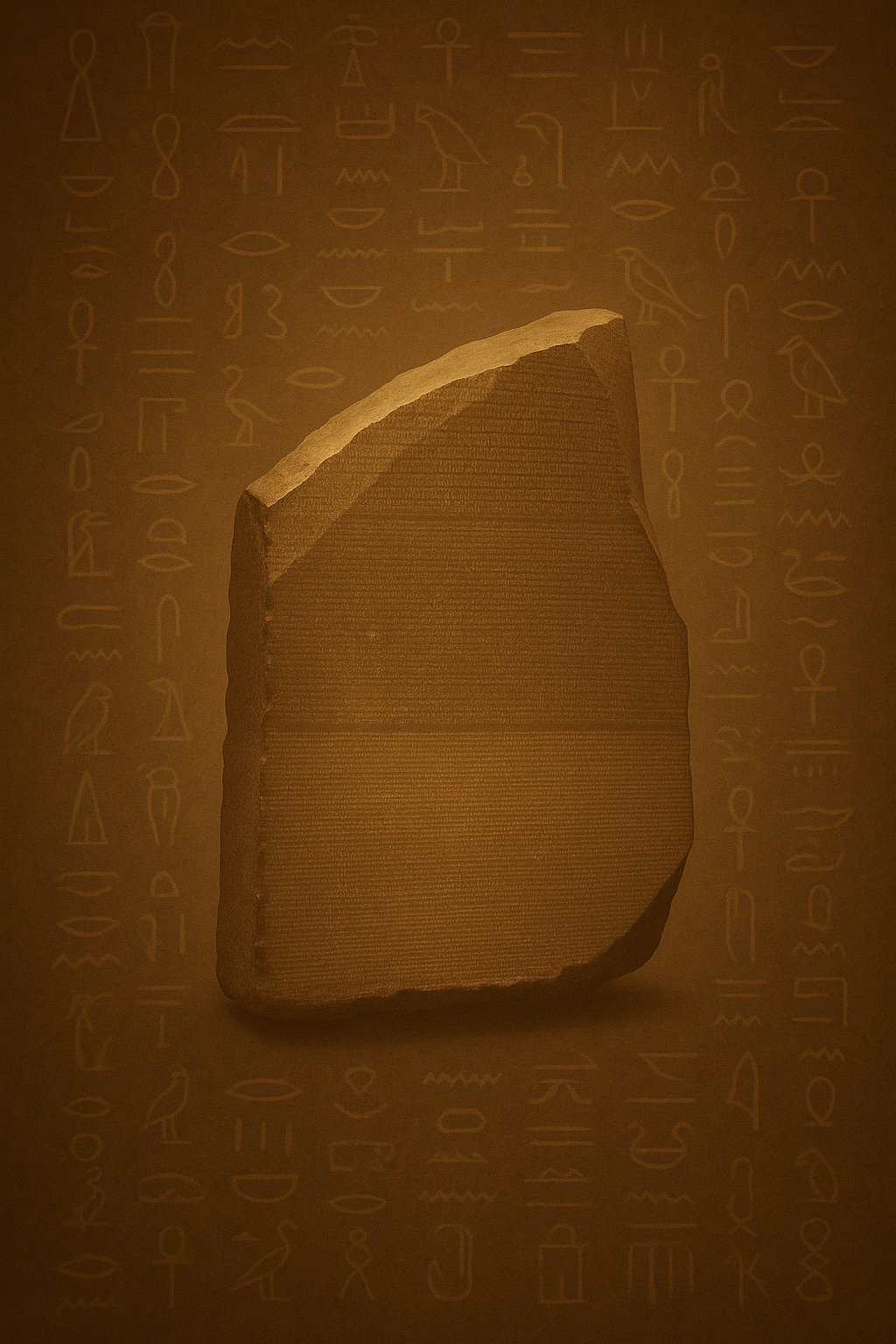

The Rosetta Stone: An Imperial Trophy

Few objects symbolize this imbalance more than the Rosetta Stone.

How Britain Seized the Rosetta Stone

Discovered by French soldiers in 1799 near Rashid (Rosetta) in Egypt, it was seized by the British in 1801 after Napoleon’s defeat and shipped to London. Since 1802, it has sat in the British Museum.

Why Egypt Continues to Demand Its Return

Egypt has repeatedly requested its return, arguing that the stone is a cornerstone of its own history and scholarship. If Britain is serious about confronting its imperial past and building new relationships with formerly colonised nations, returning the Rosetta Stone would be a powerful place to begin.

The Benin Bronzes: Looted in War, Scattered Worldwide

In 1897, British forces launched a punitive expedition against the Kingdom of Benin (in present-day Nigeria).

The 1897 Punitive Expedition Against Benin

They invaded the royal palace, burned much of the city, and seized thousands of brass and bronze plaques, statues, ivory tusks, and other sacred objects. These works are now famous as the Benin Bronzes.

Many pieces were sold to museums in Britain, Germany, Austria, and the United States to offset the cost of the invasion. A few have recently been repatriated:

- Germany, the Smithsonian,the University of Cambridge, theUniversity of Aberdeen, and others have begun returning bronzes to Nigeria.

- More European countries have announced frameworks for restitution, especially for objects acquired in colonial contexts.

The Controversy of “Long-Term Loans”

Yet even as some bronzes go home, many institutions still propose “long-term loans” of Benin art back to Nigeria—a suggestion widely criticised as absurd and neo-colonial.

You cannot “loan” a people what was stolen from them.

The Bangwa Queen: Cameroon’s Displaced Majesty

How the Sculpture Was Removed and Sold

The Bangwa Queen of Cameroon, a 32-inch wooden figure of deep spiritual significance, was removed around 1899 by German colonial agent Gustav Conrau. From there it passed through dealers and collectors, ending up in European and American hands.

H3: The Financial Exploitation of African Heritage

In 1966, it was purchased for about $29,000; decades later it sold for millions of dollars at auction. None of that profit went to the Bangwa people, whose cultural heritage had been turned into speculative investment.

The Maqdala Treasures: Ethiopia’s Loss and Resistance

The 1868 British Invasion of Maqdala

During the 1868 British invasion of Maqdala (Magdala), the stronghold of Emperor Tewodros II of Ethiopia, British forces looted an extraordinary array of treasures: crowns, ceremonial crosses, shields, royal garments, manuscripts, and religious objects. Contemporary reports note that fifteen elephants and two hundred mules were required to carry the plunder down the mountain.

Partial Returns and Persistent Refusals

Some of these items sit in British museums to this day. In 2021, a small number of Maqdala items were returned to Ethiopia through the efforts of a British nonprofit and private negotiation. But many of the most sacred objects—such as the Tabot, a representation of the Ark of the Covenant—remain held in the UK and are not even placed on public display.

The Story of Prince Alemayehu

Prince Alemayehu, son of Emperor Tewodros II, adds a further wound. Taken to Britain as a child, he died at 18 and was buried at Windsor Castle. Ethiopia has repeatedly requested the return of his remains. The answer has been no.

Beyond the Glass Case: Digital Copies and New Forms of Extraction

Even as physical artifacts remain abroad, a new layer of control is emerging: digital ownership.

The Rise of 3D Scanning and Digital Ownership

Many museums now create high-resolution 3D scans and images of African works in their collections. These can be used for virtual exhibitions, educational resources, and sometimes even sold or licensed.

Ethical Questions About Digital Profits

While digitisation can expand access, it also raises ethical questions:

- Who controls the digital copy of a stolen object?

- Should European institutions profit from licensing images of artifacts that were never legitimately theirs?

- How can African countries and communities assert rights over both the physical object and its digital presence?

Without clear agreements, digitisation risks becoming a modern extension of the same extractive mindset: Europe holds the originals and also owns the data.

The African Diaspora and the Emotional Weight of Return

For African diasporic communities in the Caribbean, the Americas, and Europe, these artifacts are not just museum pieces. They are material links to histories that were violently disrupted by slavery and colonialism.

How Stolen Art Deepens Diasporic Disconnection

Seeing Benin Bronzes in London or Bangwa sculptures in Paris can be both moving and painful. They confirm the depth and sophistication of African artistic traditions—while also reminding viewers that much of this heritage is still controlled by the descendants of those who plundered it.

Restitution as Cultural Healing

The restitution movement is therefore not only about states and museums. It is also about how Black people around the world rebuild memory, pride, and connection to the continent.

The Economics of Stolen Art

How Africa Loses Tourism and Cultural Revenue

There is also a hard economic dimension. African countries lose out when their most iconic objects sit in European museums:

- They cannot build major exhibitions around treasures that are not physically present.

- They lose tourism revenue, research opportunities, and global visibility.

- Meanwhile, Western institutions attract millions of visitors and substantial income on the back of these holdings.

Returning key artifacts would help African museums and cultural centres grow into the world-class institutions they are already striving to be—places that young Africans can visit to see their own history in full, not in fragments.

A Changing Landscape? Progress and Pushback

In the last few years, there have been important shifts:

- Several European countries, including Germany, Belgium, and the Netherlands, have developed policies specifically for returning colonial-era looted objects.

- Universities and small museums have sometimes moved faster than large national institutions by researching provenance and initiating returns.

- African governments and curators are planning or expanding museums that can receive repatriated works—such as Nigeria’s planned Edo Museum of West African Art.

Why Institutional Resistance Persists

At the same time, there is resistance. Some officials worry that returning artifacts will set a precedent they cannot sustain. Others argue that Western museums are “safer” or “better equipped,” ignoring the fact that many of these same institutions were built with wealth generated by colonial exploitation.

What Justice Could Look Like

True restitution goes beyond the occasional high-profile return. It could include:

- Systematic provenance research, funded by the institutions that currently hold the objects.

- Full and unconditional repatriation of items clearly taken through violence, coercion, or theft.

- Shared curatorship and expertise, with African scholars and communities leading narratives about their own heritage.

- Ethical digital agreements, ensuring that African countries hold rights over the digital images and scans of their artifacts.

- Investment in African museums, archives, and training, not as charity, but as delayed justice.

A Final Word: Time to Come Home

At the heart of all this is a simple ethical principle:

you cannot build a story of “universal” culture on foundations of theft and deny the victims a say.

These objects are not neutral works of art. They are royal regalia, sacred embodiments of ancestors, chronicles of resistance and creativity. They carry the memory of people who carved, cast, wore, kissed, and prayed over them.

As the Ife head sits in British custody, as the Rosetta Stone remains in London, as the Benin Bronzes, the Bangwa Queen, and the Maqdala treasures continue to live abroad, one truth grows harder to ignore:

They are not European souvenirs. They are African histories. And they deserve to go home.